Dream Spaces: The Linderman Mansion

Fishers Island, NY

A common refrain for my family during our summers spent on Cape Cod: we pass a house, close to the water, cedar shingled but enormous. One of those Chatham compounds that start at a cool two to three million. We point and announce: “Garp house.”

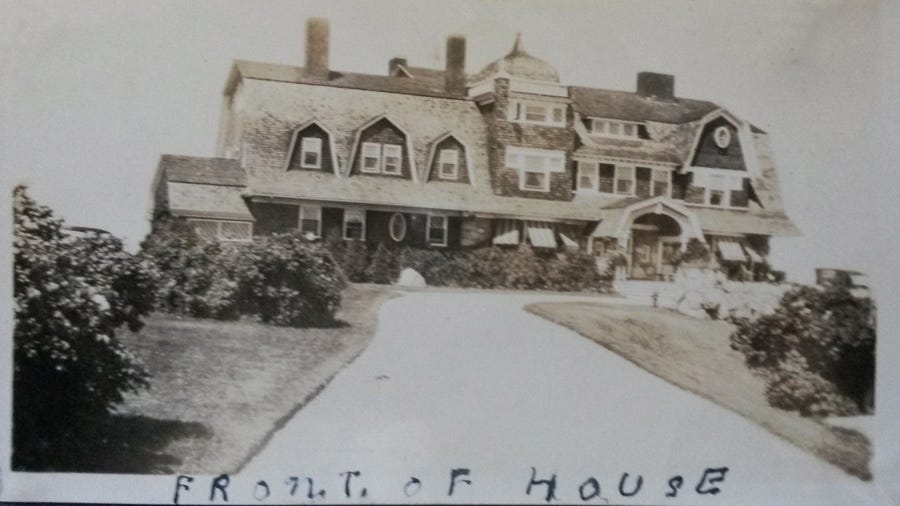

The World According to Garp is a John Irving novel I like, and a George Roy Hill film I love. In the book, aspiring novelist T.S. Garp comes of age against a variety of scenic backdrops, including his mother, Jenny Fields’s—a nurse and author of a prominent feminist manifesto—family home, Dog’s Head Harbor in New Hampshire. But in the film adaptation, Jenny’s home was filmed on location at the expansive Linderman Mansion on Fishers Island, New York. The house is massive and jaw-dropping: outfitted with turrets, sweeping porches along the front and backside, and nestled atop a hill overlooking Hay Harbor. In all its grandeur, it’s still unmistakably New England with its cedar meets stone composition.

The film occupies a tender part of my heart, becoming somewhat of a marker of essential transition moments, and I find myself returning to it often. My father gave me a copy of it the night before I left for college and I wielded the DVD as mandatory viewing for my freshman dorm-mates. My best friend and I watched it during our first month living in Brooklyn, twenty-two and directionless, unable to suspect how our lives would shake out. I watched it on Christmas Eve a few years ago with my husband, then as friends. We kissed somewhere midway along the movie and decided by the time the credits rolled that we wanted to be together.

I find new things to love every time I return to the film, but its primary draw remains consistent. Tragedies befall the Garp family, and the adaptation does a rather miraculous job with its soft depiction of the beauty and joy that still exists after the foregone conclusion of death and subsequent suffering. When the family retreats to the compound after a major loss, Jenny (played to perfection by Glenn Close in her film debut) puts her nurse hat back on. “There’s a lot of healing yet to be done,” she says. The house feels emblematic of healing. Bustling, saltwater adjacent, with enough room for true leisure and privacy if you seek it.

What constitutes a dream space? In mine, no matter how disparate the aesthetic or locale, there seems to be a common thread running among them: restricted access. A hotel that costs more than a month’s rent or mortgage for a single evening’s stay. A family summer house with a deed that changed hands and switched locks during a desperate, shady business deal. Fishers Island is utterly inhospitable to those who are interested in it. There are no overnight accommodations on the island—hotels long gone, no AirBnbs, limited seasonal rentals—and ferrying made intentionally difficult by a single, inconveniently located origin point in Connecticut.

A New York Post article dated August 2001 (ah, a simpler time) proclaimed how old money still ruled and constricted Fishers Island, citing everything from its minuscule town center (three stores, one bar, one market) to its….borderline anti-Semitic homogeneity? (“‘It looks like one big Polo ad without a Ralph Lifshitz in sight,’ jokes a recent visitor of the island’s lack of ethnicity.”) 250 WASP-y residents live there year round, calling the island “the last bastion of civility.” A 90s-era rumor about a notorious real estate industry con man (don’t make me type his name) coveting the island’s historic Simmons Castle sent shockwaves through the community, giving way to their collective sigh of relief when he changed his mind. (Of course, he eventually set his sights on a different giant house—that white one on Pennsylvania Avenue—and tormented us all. But happy for the WASPs of Fishers to have avoided his local presence!)

The Garp house has changed hands—and names—several times since it was built at the turn of the 20th century. Commissioned by the heirs to the Bethlehem Steel fortune, the Linderman family, the house has also been owned by opera star Alma Gluck and her husband, the composer, Efram Zimbalist. “Father of Rayon” Samuel Salvage owned the property through the 1930s and 1940s, before the house eventually went to his wife’s nephew, David Wilmerding, who occupied the property when Garp was filmed and voiced his irritation at the influx of attention on his house following the film’s release. It’s been reported that the most recent owners of nearly twenty years, Peter and Katie Bacille, conducted a major renovation on the house—making it unlikely that any trappings that once defined Jenny Fields’s space remain intact.

This is a dream space that will remain within a dream. I could get myself to Fishers Island for a limited day trip, but I wouldn’t be able to get close to the house. I’ll never get to sit on the porch or in Adirondack chairs on the lawn like the Ellen James Society members that Jenny welcomed into her home, or run my hands along the oak bannisters of the staircase. In the moments where I have the clarity to recognize all my healing yet to be done, I crave this house—a house I’ve never stepped foot in and never will. But the longing always finds a way towards invention: a conjuring of methods, how to heal within the walls I already occupy.

Such a wonderful essay about an iconic house. My father grew up on the island, and my parents moved there when they retired. My Mom was an extra in the movie. They filmed her in two scenes. One landed on the cutting floor, the other is about 2 seconds in the "Christmas" scene. I know several other extras in the movie.

Fuck you. Eat the rich.