Love in the Age of a Fire Curse

I had a dream the other night I was standing inside the bones of a house, all beams and outlines, nothing fully built. My maternal grandfather—a man of impeccable taste and also dead five years now—was standing in what was to become the living room, showing me bricks he planned to use on an interior wall. “It’s lovely,” I told him, “but why are you building a house in a war zone?” A smokiness in the air had become impossible to ignore. He smiled and I woke up before I got his answer. It was 1:47 in the morning and the air in my bedroom was actually heavy with the smell of smoke.

I leapt out of bed and ran out to our balcony where I observed no visible fire, but was surrounded still with the thick charred smell, stronger even than in the bedroom. I skulked around each room and floor of the apartment, all of it cloaked in the nauseating scent. The windows in our living room were open so I slammed them shut. No fire alarms. Nothing recent or urgent according to a quick Twitter search. I was about to wake my husband when I thought to check NextDoor—a new-to-me platform that had thus far appeared to be little more than a digital playground for middle aged locals sharing posts about lost cats. “Anyone smell a fire?” someone had posted. Twelve insomniac angels corroborated the sensation in the comments below, sharing links to news articles to a forest fire that had occurred earlier that evening, about 50 miles south in Little Egg Harbor. One included a trajectory of the resulting smoke, a hovering black cloud over Asbury Park and stretching far beyond.

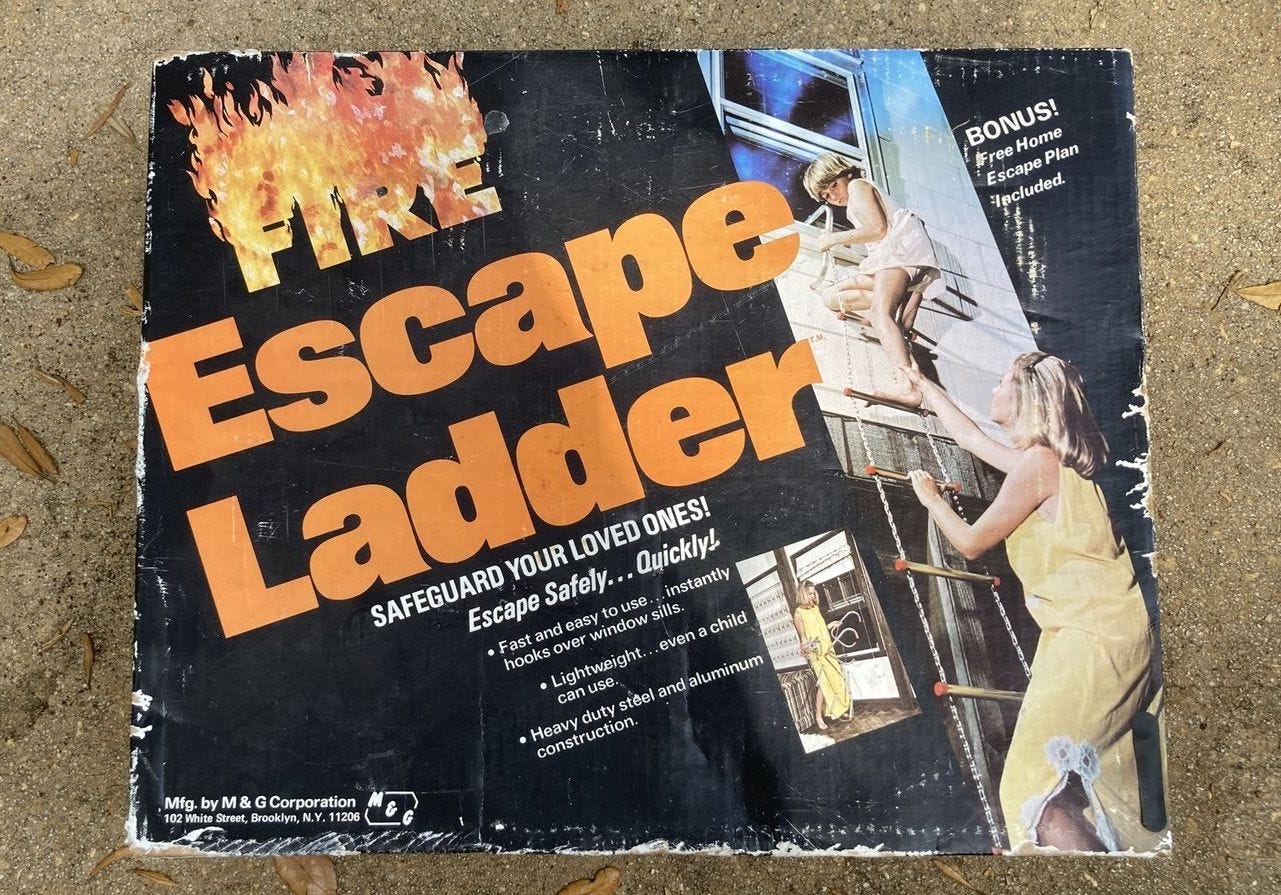

My anxiety is a force that solicits irrational fears all day long and I work exhaustively to mitigate it. But I consider the threat of fire to be a wholly rational fear of mine, one of the few in the category. I suspect this was something I was born into: my mother never slept without a roll-down aluminum fire escape ladder in her closet from the time she was ten years old. She still recalls watching the news with her father (the aforementioned grandfather who built a house in the war zone of my dreams) on a Sunday morning in the early 1970s and seeing a devastating house fire flash across the screen. The image was coupled with a chyron: A Father’s Day to Remember With Horror. Seconds later, my grandfather recognized the house as one belonging to his close friend—my mother’s “Uncle” Tony in Bay Ridge—and ran out the door to drive over. The family survived, but Tony only narrowly escaped from the second story after having to toss his two young daughters into the arms of strangers before leaping out the window himself. My mother saw him often after, marveling at how his arms and his neck—pink and marbled—turned the momentary flash of a fire into evidence he’d bear forever.

Perhaps I inherited some cell memory of the experience my mother bore witness to, but I feel justified in my fear of fire because I married into a fire curse. Before I’m accused of my usual propensity for being hyperbolic, allow me to elaborate. My husband’s maternal grandparents and all arms of their immediate family have suffered freak fires, one each in three concurrent decades. The first was in a fraternity house where his uncle lived, which burned after a couch was set aflame. The next was in a house jointly-built and owned by my husband’s parents and grandparents, which burned after a mishap involving a Christmas village setup, an electric Hummel figurine ice skating set, and perhaps a little too much fake snow. The third was in a historic home not far from where we live now, purchased by his aunt’s family shortly before burning down in the middle of the night—the result of a fire that started between the walls of the house.

Thankfully—and rather miraculously—everyone survived these incidents and no one was injured. But traces of the impact of these fires remain. Lux-looking candles around the families’ homes that are in fact battery operated, a waving plastic “flame” occupying the wax dip where a wick should be. Entire eras of personal history erased with the instant disappearance of photographs and documents. Nana Pat—the family matriarch and a superb stand-in for my quartet of beloved grandparents, whom I am now without—presented me with a sooty bible to carry at my wedding. It was one of the few things she was able to salvage from the Christmas village fire. Other heirlooms and some remaining photographs she’s shown me are, to borrow a phrase from Amy Hempel, bordered with scorch. In the picture boxes where the memories of whole decades should be, there are instead folded newspaper clips documenting the family fires. Grim placeholders to remind us why we can’t find what we’re in search of. Recently, Pat revealed to us rather casually that the Boston area hospital where she was born famously burnt to the ground. Perhaps it was the spark that ignited the family curse.

About two months ago, on the morning I was to receive my second COVID vaccination, I attempted to get some early work done to account for the time I’d be out in the afternoon when a wave of strong chemical fumes blew through the window. I dismissed them as fallout from ongoing construction nearby until the alarms started going off. Not our shrill smoke detector alarms that are wont to chirp every time I broil a piece of salmon too long, but the blaring honks and flashing lights of the building-wide emergency alarms meant to signal an evacuation. I grabbed my keys, my vaccination card, and little else as I sprinted out the door, still in my pajamas. I was in the hallway when a boom erupted, shaking the floor beneath me, catapulting me into fight or flight mode. I flew down the stairs of the nearest exit, a passageway shared with the theatre that occupies the ground level space below my apartment. I opened the door to black smoke, flames sprouting out of manholes in the street, and an alphabet at my feet. The explosion had knocked all the letters off the theatre marquee down onto the sidewalk.

Fast forward to hours later—past my racing towards the beach, snot and tears, dual rescue by my husband and my mother, and a day’s worth of post-vax displacement spent masked on my mother’s couch—when what had initially been diagnosed as a gas leak and resulting sewer fire was revealed to be an electrical fire and subsequent explosion in the basement of the theatre. Though the theatre had been taped off and deemed an “unsafe structure” according to the signs on the doors, miraculously, no one in my building was hurt. We were allowed back into our apartments by 9 p.m., just 12 hours after the incident. I’d been married just shy of two weeks. I couldn’t help wondering, was this my initiation to the fire curse?

The house we recently bought has a wood burning stove in the living room that dates back to the house’s original 1955 construction. My husband daydreams of using it to keep the house warm all winter while I have anxiety attacks about what sort of fireproof box I’ll purchase to store my family photos and journals. But short of keeping a fire extinguisher handy and longing to build a Wanda Maximoff-esque bubble of protection around us, I’m simply left to contend with a basic fear every homeowner must possess. It’s true, I have an additional factor most others don’t: a family fire curse that still burns fresh in recent-enough memory. But I have unique supports to reassure me, too: a husband who believes the fire curse is strange but not a damnation. Parents who raised me to counter anxiety with preparedness (and boxed fire ladders). On my bookshelf, I have Nana Pat’s charred bible—a reminder of danger, but also a testament to survival.